Contact Dermatitis: An Overview

Contact Dermatitis: An Overview

As the body's primary barrier against environmental insults, the skin is regularly exposed to potential noxious agents. Many of these agents can provoke a reaction known as contact dermatitis, in which a noticeable, uncomfortable inflammatory response occurs at the site of interaction.

Two forms of contact dermatitis exist. Allergic contact dermatitis is caused by lymphocyte-mediated immune responses to an allergen, whereas irritant contact dermatitis ensues after a direct cytotoxic insult to the skin (eg, a chemical burn).[1,2] Because allergic and irritant contact dermatitis can have similar clinical presentations of erythema, edema, and vesiculation, it is important to identify the correct source that triggers the reaction.

The image demonstrates contact dermatitis caused by exposure to butternut squash (Cucurbita moschata).[3]

Acute Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis is a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction that occurs when the skin is reexposed to an allergen to which it has been previously sensitized.[1,2] External contact with the allergen activates the adaptive immune system, causing previously primed T lymphocytes to release a cascade of cytokines and proinflammatory factors.[1] This response leads to the formation of a well-defined, erythematous plaque and characteristic intercellular edema in the epidermis. The severity of the reaction is dependent on the properties of the allergen, the contact duration, and the host response, but it usually includes the formation of pruritic papules and vesicles (shown here in a 3-year-old patient 1 day after exposure to poison ivy). The vesicles can blister and ooze, with eventual crusting.[1]

Common causes of acute allergic contact dermatitis include poison ivy and nickel contact. Textile dyes are often overlooked sensitizing agents.[4] Although laundry detergents are frequently implicated by patients and physicians alike, allergic contact dermatitis to detergents is actually quite rare.[5] Topical corticosteroids are the first-line treatment for acute allergic contact dermatitis.[1,2] Other options include nonsedating oral antihistamines and topical moisturizers.

Nickel is one of the most common sensitizers that trigger allergic contact dermatitis. This metal is routinely used in jewelry, buckles on clothing, kitchen supplies, and even medical devices. An individual who is allergic to nickel can develop a pruritic, erythematous plaque that precisely demarcates the area of contact. In the acute phase, erythema is accompanied by edema and vesiculation, whereas chronic exposure can cause lichenification and pruritus.[6]

Although topical corticosteroids can be administered to alleviate the reaction, strict avoidance of nickel is the recommended management. In severe cases, even systemic exposure to nickel may provoke skin reactions. Persons with extreme sensitivity may also need to avoid foods containing nickel, such as chocolate, oatmeal, nuts, and green beans; these individuals may benefit from treatment with disulfiram, a metal-chelating agent.[6,7]

The presence of nickel in a watch and watch band produced the episode of allergic contact dermatitis shown.

Severe Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Severe reactions to exogenous allergens can occur. Paraphenylenediamine (PPD) is a common ingredient in hair dyes that can cause allergic contact dermatitis.[2,8,9] Acute dermatitis and severe facial edema may develop following exposure to PPD in hair dye products.[2] Treatment options for severe reactions include systemic corticosteroids, antibiotics, immunosuppressive agents, and hospitalization.[2] Unfortunately, in patients with PPD allergy, there is a high rate of cross-reactions with PPD-free hair dyes, and most affected patients must completely discontinue hair dye.

PPD is also found in temporary tattoos, which can cause severe allergic contact dermatitis in a sensitized individual.[2] Black henna tattoos contain PPD, whereas red henna tattoos do not.

The image demonstrates edema and erythema as a reaction to henna pigments in the tattoo.

Chronic Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Long-term exposure to an allergen can lead to the development of chronic allergic contact dermatitis. This condition is typically characterized by hyperpigmented, lichenified plaques that are exacerbated by scratching.[10] In affected areas, such as the hands, painful fissures and dry scaling are common. Identification of the allergen is critical to reducing the risk of repeated allergen exposure and subsequent development of chronic allergic contact dermatitis. Treatment options include topical or systemic corticosteroids, emollients, phototherapy, and immunosuppressive agents.[2]

The image shows the sequelae of repeated exposure to wet cement on the hand of a construction worker. Chromates, contained in cement, are among the most common sensitizing agents in the construction industry.[1,11,12]

These images show occupational allergic contact dermatitis in an Indian construction worker. The left image reveals discrete papular eruptions on the arm with relative sparing of the trunk. The right image, in the same patient, demonstrates similar eruptions over the proximal portions of the dorsal hands but with sparing of the fingers.

Acute Irritant Contact Dermatitis

The majority of contact dermatitis cases are caused by direct exposure to irritants (as opposed to the immune response of allergic contact dermatitis).[13] Irritant contact dermatitis is a nonimmunologically initiated inflammatory response to localized exposure to a cytotoxic agent. Hazardous agents—including surfactants, solvents, acids, and alkaline solutions—are commonly encountered in the workplace and at home.[14,15] The three most common exposures are rubber, wet work, and soaps and cleansers.[15]

Treatment options include thorough flushing of the skin with water, followed by the use of topical corticosteroids, oral antihistamines, emollients, cold/moist compresses, moisturizers, antibiotics, and/or antidotes/agents that act specifically against the offending irritant.[15]

The image shows ulcerations on the back of a hand 44 hours after exposure to sodium hydroxide solution (lye), a strong base that is frequently used as an industrial cleaning agent.

The acute form of irritant contact dermatitis is caused by direct tissue damage. After chemical or physical irritants penetrate the epidermal barrier, keratinocyte injury promotes the release of proinflammatory factors that lead to leukocyte recruitment.[14,16] The reaction will occur in minutes to hours after the initial contact, consisting of burning, stinging, or soreness at the area.[16]

Irritant contact dermatitis is a leading cause of occupational skin disease.[15] The clinical features of irritant contact dermatitis include a wide range of presentations of erythema, edema, and bullae; the findings depend on the nature of the irritant. For example, ulcerations will form in the presence of inorganic acids and strong alkalis, whereas folliculitis will develop after contact with greases, tar, or asphalt.[15] An eczematous process can occur in those who handle or clean crustaceans, such as shrimps, crabs, and lobsters.[17]

The image shows cellulitis and irritant contact dermatitis on a patient's left arm following exposure to parenteral organophosphate.

Chronic Irritant Contact Dermatitis

Chronic irritant contact dermatitis (shown) results from a different pathophysiologic mechanism than does the acute form, with repeated exposures to solvents and surfactants causing slower damage to keratinocyte cell membranes.[15,16] Solvents, including hexanes found in gasoline and benzene found in plastics and resins, remove surface lipids from the stratum corneum. Surfactant, found in many detergents and cleaning agents, binds to keratin and causes protein denaturation. This disruption of barrier function promotes transepidermal water loss and desquamation.

In some individuals, irritant contact dermatitis resolves spontaneously even with ongoing exposure, perhaps as a consequence of thickening of the stratum corneum resulting in improvement of the physical barrier.[18] Chronic irritant contact dermatitis develops when the irritant contact frequency is greater than the time needed for recovery through barrier restorative mechanisms, such as lipid synthesis and keratinocyte proliferation.[15,16]

Areas of chronic irritant contact dermatitis are less defined than those seen in the acute form. Lichenification and hyperkeratosis are characteristic features of chronic irritant contact dermatitis, and they are associated with pain and pruritus of the affected areas.[15]

The skin, hands, and wrists of this man demonstrate the sequelae of long-term exposure to kerosene, a solvent. Kerosene was routinely used to clean the skin by workers who had contact with oily products (eg, auto mechanics), resulting in eventual thickening, fissuring, and hyperpigmentation.

Phytodermatitis

Poison ivy

Plants are a common cause of both allergic and irritant contact dermatitis; this is known as phytodermatitis. The characteristic skin lesions are linear eruptions.

Poison ivy is the most common cause of allergic phytodermatitis[19] and is in fact the overall most common cause of any skin allergy. Over 95% of humans are allergic to poison ivy. This plant contains the compound urushiol, which causes a pruritic eruption (shown) within 2 days of contact; left untreated, the eruption can persist for 2-3 weeks. Streaks of erythema, edema, and papules are typically observed before the formation of vesicles and bullae (as shown on slide 2). Vesicles will not develop if the antigen load is low.

It is a common misconception that the rash of poison ivy is contagious. Fluid in the bullae does not carry noxious particles; therefore, bullous eruption does not propagate the reaction.[19]

Glochids

Plant-induced irritant contact dermatitis can be mechanical or chemical. Mechanical insults can arise from contact with thorns or spines that penetrate the skin, with the smallest spines causing the most damage. Glochids covering the surface of prickly pears are especially notorious for these skin reactions. The collections of hundreds of short, barbed spines act like fishhooks in the skin, causing pruritic, papular eruptions.

The most common chemical cause of irritant phytodermatitis is calcium oxalate, which is found in daffodil, pineapple, rhubarb, and century plants. The skin reactions to calcium oxalate are typically a burning sensation and the formation of blistering lesions.[19]

The left image shows irritant phytodermatitis after contact with the glochids of Opuntia microdasys monstrose, a type of cactus. The right image is a scanning electron micrograph of the retrorse barbs at the margin of a Hordeum murinum spikelet. H murinum is a type of annual grass.

Stinging nettle

The stem and leaves of the stinging nettle plant (Urtica dioica) are covered in tiny trichome hairs (shown) containing histamine. Upon contact, these trichomes inject histamine into the skin, causing an itchy reaction known as contact urticaria.

Phytophotodermatitis

Phytophotodermatitis is caused by contact with a botanical photosensitizing agent followed by exposure to sunlight.[19] Furocoumarins, the most common causative agents, can be found in some members of the family Rutaceae (eg, limes, grapefruit, garden rue), where they function as biologic microbicides.

In the presence of ultraviolet A (UVA) radiation, furocoumarins form reactive oxygen species that can rupture keratinocytes in the epidermis and increase melanocyte activity.[19] Erythema, edema, and bullae appear 24 hours after contact, followed 1-2 weeks later by the appearance of hyperpigmentation. These reactions are painful but nonpruritic, and they are generally self-limited.[20]

The image shows erythema and early bulla formation on the left arm of a horticulturalist. Exposure to the garden rue (Ruta graveolens) caused the phytophotodermatitis.[19]

Limes are a common cause of phytophotodermatitis. The typical scenario involves a patient who has traveled to a sunny location for vacation and has been mixing drinks with limes. The rind of the lime contains 8-methoxypsoralen, a furocoumarin compound. In this photo, a patient shows blistering where lime juice dripped down her dorsal forearm. The woman, an airline flight attendant, had contact with limes while serving drinks on a flight to the Caribbean and then had significant sun exposure during her layover there.

Acute treatment options for phytophotodermatitis include removal and avoidance of the offending agent and the use of cool, wet compresses. More severe and edematous reactions may require the administration of topical corticosteroids or indomethacin; patients with very severe reactions (where >30% of the body is affected) are generally admitted to a burn unit for local wound care.[20]

Patch Testing

Patch testing is the gold standard diagnostic tool for the evaluation of allergic contact dermatitis.[14] Identifying the specific allergen can help clinicians to distinguish between allergic and irritant contact dermatitis, which, as previously noted, have similar clinical presentations.

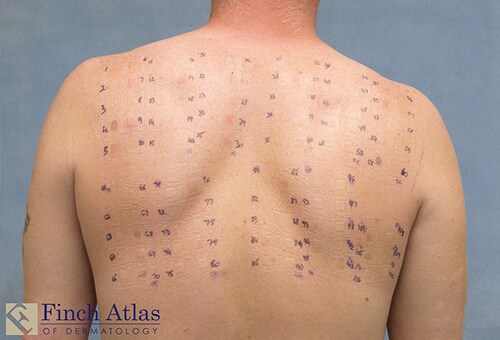

Obtaining a detailed history is critical for identification of common exogenous exposures at work and at home. This information will help to direct the selection of appropriate agents (examples shown) to be included in an individual patch test.[2,14]

Patch testing is usually conducted on the patient's back (shown), where controlled concentrations and volumes of allergens are aliquoted into chambers (as shown in the previous slide, at the top of the image) and secured to the skin using tape. It is important that the area be kept dry for the duration of the test (96 hours). The patient is instructed not to immerse the area in water.

After 48 hours, the patches are removed. The locations of the patches are marked with a gentian violet skin pen, and each site is systematically classified and graded[1,14] on the basis of its morphologic features (eg, erythema, edema, papules, vesicles, bullae) and intensity.[14]

After 96 hours, the patient returns to the dermatology clinic, and a second, delayed assessment is performed. A positive reaction at both the preliminary 48-hour reading and the delayed 96-hour evaluation is a stronger indicator of an allergy than is a transient reaction that occurs at 48 hours but resolves by 96 hours.

Redness and induration are graded as a 1+ reaction. Vesicle formation is graded as a 2+ reaction, and bulla formation is graded as a 3+ reaction.

In this case, the patient was patch tested because she had a long history of mouth and lip dermatitis. Patch testing confirmed a severe allergy to ethylethacrylate (top, 2+), tetraethylene glycol dimethacrylate (middle, 3+), and methyl methacrylate (bottom, 3+)—three acrylic polymers used in her dental implants.[21]